The Truth about 1938

In setting The Truth According to Us in 1938, I had two motives. The first I’m not telling, but the second was purely dictated by the facts of history. In order to get my characters where they needed to be, it was necessary to have my story coincide with the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal jobs program that clawed its way into existence in 1935 and was torn asunder by politicians in 1943. Though the Project was more or less fighting for its life the entire time, the period between 1937 and 1939 could be considered its heyday, an era of relative administrative serenity and high productivity. With that mathematical acumen for which I am renowned, I split the difference and got 1938.

In setting The Truth According to Us in 1938, I had two motives. The first I’m not telling, but the second was purely dictated by the facts of history. In order to get my characters where they needed to be, it was necessary to have my story coincide with the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal jobs program that clawed its way into existence in 1935 and was torn asunder by politicians in 1943. Though the Project was more or less fighting for its life the entire time, the period between 1937 and 1939 could be considered its heyday, an era of relative administrative serenity and high productivity. With that mathematical acumen for which I am renowned, I split the difference and got 1938.

So I set the story in 1938.

This is like reserving the hall, and then deciding whom you’ll marry in it.

I suppose I had a basic working understanding of the year’s major events, which could be summed up by the headline “Not Good.” In the United States, 1938 was the year of the secondary Depression, unless you were one of those who hadn’t recovered from the first Depression, in which case it was the same old Depression. Overseas, the situation was grim and trending downward. In Europe, the menace of Hitler’s territorial ambitions ceased to be theoretical and became disastrous reality in Austria and Czechoslovakia, while his genocidal intentions grew ever more overt, culminating in the Kristallnacht pogrom in November. In other European developments, the Fascists were triumphing over the forces of good in Spain, England was pursuing a policy of appeasement with Germany, as was Russia. France was  pursuing a policy that could have been called If We Don’t Pay Any Attention, Maybe They’ll Go Away, and every nation was arming itself to the teeth. In the eastern hemisphere, Chinese forces were giving ground, inch by inch, in the second year of what would be an eight-year war with the empire of Japan, which was concurrently plotting the invasion and domination of the entire Pacific region.

pursuing a policy that could have been called If We Don’t Pay Any Attention, Maybe They’ll Go Away, and every nation was arming itself to the teeth. In the eastern hemisphere, Chinese forces were giving ground, inch by inch, in the second year of what would be an eight-year war with the empire of Japan, which was concurrently plotting the invasion and domination of the entire Pacific region.

But this is history told from the vantage point of the twenty-first century. I know 1938 in terms of what I perceive to be the inexorable path to World War II. Both the frantic efforts to avoid it and the ominous markers of its approach are to me the story of that year. But what if you lived during it? How would that time be experienced? The second world war looms so large in our perception of our individual selves—and even larger in our perception of America’s identity—that it takes a massive feat of imagination to remove it, or block it out, even very temporarily. To catch a glimpse of a small town in America, not “before the War,” or even “before people realized War was inevitable,” but without the inevitability—well, it’s nearly impossible. I picture it as something like trying to isolate one of those new, desperately unstable elements on the periodic table, ununhexium, say. It can be done, but only after bombarding leaden reality into shards, and even then, only for a millisecond.

What I wanted was to know not just what happened (which is, semantics aside, not that difficult), but how it played. I wanted to know where certain kinds of phenomena ranked in the consciousness of the era. What kinds of associations were made with various images and words and what aspirations were so widely held that they could be assumed across the culture. What values were so widely understood that individuality was measured by divergence from that norm?

Obviously, culture is not uniform and never will be. Each of us manifests, relates, consumes, converses, deploys, and propagates in a manner differing in a thousand, a million, an infinite number of ways from the person standing beside him. But even so, there are group understandings, shared ideas about what the conventions of the culture are. If there weren’t, there would be no such thing as jokes. And those group understandings were the treasure I was seeking as I combed through books, magazines, newspapers, movies, songs, cartoons, catalogues, recipes, menus, headstones, artworks, yearbooks, photographs, graphics, slogans, and architecture of the late 1930s.

My research methods certainly weren’t scientific, but neither was the information I was trying

to obtain. Let’s take, for example, women’s shoes.

If I had simply wanted to know the price of women’s shoes in 1938, I would have flipped through the Sears catalogue until I found this page, and then moved on. Instead, I lingered in the shoe department for hours, seeking the universal assumptions that were being made about women’s shoes. Was it assumed that women wanted to be sexy or thrifty? Or both? If sexy, were they assumed to want to be cute, beautiful, glamorous, similar to a famous figure, sexually available, impressive, mysterious, or what? If thrifty, were they assumed to want to be known as thrifty or to be thrifty while masquerading as prosperous? What about heel height–was tall good, not so good, or neutral? What heel height catapulted the wearer into floozy-hood? Did black shoes have connotations of sobriety or sophistication or mourning or nothing? What did worn heels signify, and how worn could they be before it was imperative for a shabby-genteel white woman to buy new ones? How many shoes were expected in the repertoire of that same shabby-genteel white woman in a small town? How many would be seen as profligate? And if one were shoe-profligate, was it likely to be regarded as a vanity or a more serious crime? With regard to styling, who wore T-straps? Who wore shoes with perforated decorations? Was patent leather the province of the young? How important was matching one’s shoes with one’s clothes? One’s shoes with one’s purse? Were there class implications to a clutch versus a purse with a handle?

If you spend enough time with a Sears catalogue, you can answer many of these questions.

Luckily, the mechanism of advertising has remained unchanged since (probably) the beginning of time. All ads employ one (or more!) of the following four strategic propositions:

- You should be more afraid

- You should be sexier

- You should be richer

- You should be happier

This fortunate consistency allowed me to mine ads from the 1930s for information about what the society feared, what was considered sexually desirable, the standards of prosperity and poverty against which acquisition was placed, and the (remarkably uniform) definition of happiness.

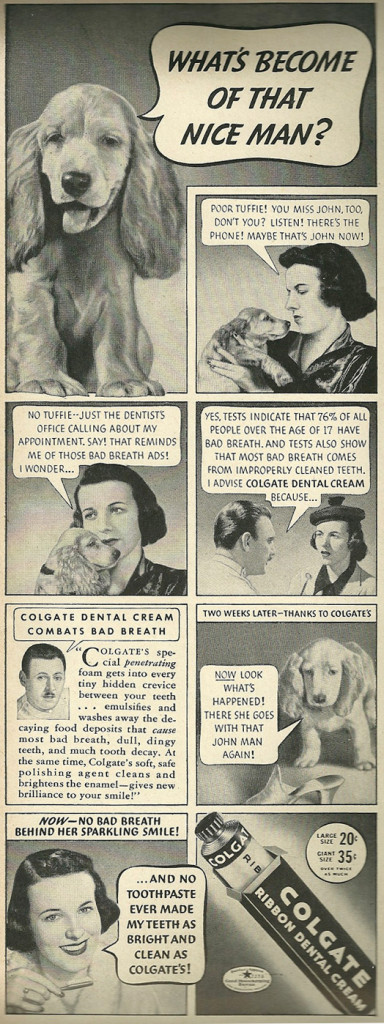

One of the great preoccupations of the era was bad breath. This is typical of hundreds of ads that happily combine all four advertising strategies into one persuasive message: if you have bad breath (be afraid), you’ll lose your man (be afraid), so use Brand X toothpaste, which is economical (be richer). Your breath will be great (be sexier) and your man will come back (be happier). Very nice, but what are the conventions that buttress this message? Obviously, toothpaste itself has societal acceptance; this is not toothpaste-advocacy, but brand-advocacy. Everyone’s brushing their teeth, but many people (76%) are doing it wrong. Further exegesis reveals that we’re in a world where middle-class people have dentist appointments and where dentists are perceived as scientists. On a more sociable note, we learn that dates were made by phone; that marriageable girls wore tam-o-shanters and mule-style slippers; that spaniels were perceived as cute; and that the desirability of a pleasant-looking but not glamorous girl was both accepted and perceived as a reasonable ambition among the target audience (which was presumably similar girls). Less conclusively, we might possibly deduce that two weeks was a plausible period in which one could go from spurned to engaged (our heroine is wearing a ring in the final frame.)

LIFE magazines from the late thirties are a treasure-trove of such popular assumptions and codes. Every page is freighted with ideas about the normative and divergence therefrom, making it a dictionary of the culture’s definitions of important, funny, average, shocking, uplifting, modest, showy, European, American, intellectual, powerful, pathetic . . .

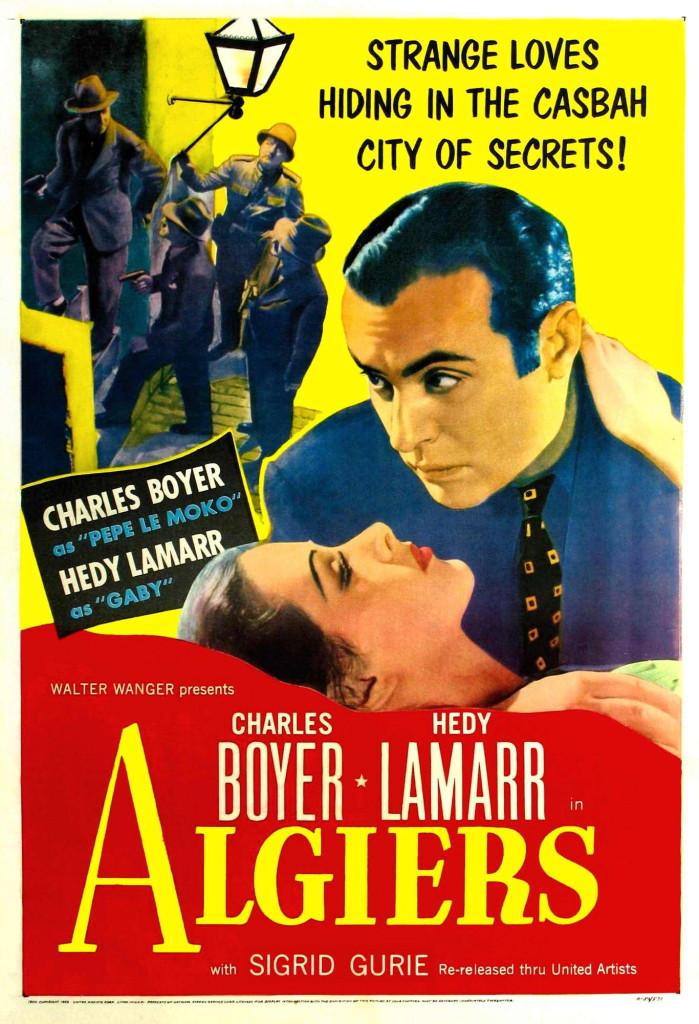

Movies, while fun to watch, were less useful than I expected, as the majority of them are by their very nature bent on depicting divergence from norms. Algiers, a 1938 release that two of my characters enjoy, is a perfectly good movie, but it tells me very little about the world in which it was made, since it is ostentatiously “exotic.” Its stereotypic French anti-hero gives me a nice round-up of traits commonly associated with Frenchness by Americans of the era (sexiness, moral dubiousness, and imperturbable suavity in the face of peril), but this information was of notably little use in writing about a small town in West Virginia. A movie that purported to be about small-town reality was Love Finds Andy Hardy, which I could not resist quoting at length in The Truth According to Us, precisely because its depiction of middle-American preoccupations was so ridiculous. While it might reveal something about the low-grade prurience and misogyny that was considered entertaining in 1938 America, and it certainly reveals accepted forms of maternity, judiciousness, youthful vigor, and modesty, not to mention received notions about middle-class décor, its stupidity poisons its relation to lived reality.

Movies, while fun to watch, were less useful than I expected, as the majority of them are by their very nature bent on depicting divergence from norms. Algiers, a 1938 release that two of my characters enjoy, is a perfectly good movie, but it tells me very little about the world in which it was made, since it is ostentatiously “exotic.” Its stereotypic French anti-hero gives me a nice round-up of traits commonly associated with Frenchness by Americans of the era (sexiness, moral dubiousness, and imperturbable suavity in the face of peril), but this information was of notably little use in writing about a small town in West Virginia. A movie that purported to be about small-town reality was Love Finds Andy Hardy, which I could not resist quoting at length in The Truth According to Us, precisely because its depiction of middle-American preoccupations was so ridiculous. While it might reveal something about the low-grade prurience and misogyny that was considered entertaining in 1938 America, and it certainly reveals accepted forms of maternity, judiciousness, youthful vigor, and modesty, not to mention received notions about middle-class décor, its stupidity poisons its relation to lived reality.

The discourse about food in this era was dominated by considerations about thrift, inflected by the possibility of public shame (the ladies at the club won’t eat my cake) and the desirability of the food of yesteryear (there’s no oatmeal like Ma’s oatmeal). Health, too, was a priority (eat yeast!), and, as ever, ease of preparation was a goal, provided that the consumers of the easily prepared food thought otherwise. Of course the central convention of the food category remains with us today: it’s a woman’s concern. Therefore, documentation about food, in any era of American history, is replete with a rich subtext of female norms, whether defined by apotheosis (My wife makes the world’s best scalloped potatoes), divergence (The little lady can’t even boil water), or development (When I married her, my wife couldn’t even boil water, but now? Try these scalloped potatoes!).

The discourse about food in this era was dominated by considerations about thrift, inflected by the possibility of public shame (the ladies at the club won’t eat my cake) and the desirability of the food of yesteryear (there’s no oatmeal like Ma’s oatmeal). Health, too, was a priority (eat yeast!), and, as ever, ease of preparation was a goal, provided that the consumers of the easily prepared food thought otherwise. Of course the central convention of the food category remains with us today: it’s a woman’s concern. Therefore, documentation about food, in any era of American history, is replete with a rich subtext of female norms, whether defined by apotheosis (My wife makes the world’s best scalloped potatoes), divergence (The little lady can’t even boil water), or development (When I married her, my wife couldn’t even boil water, but now? Try these scalloped potatoes!).

I was particularly entranced by the little recipe pamphlets that were commonly distributed by manufacturers of the time: “Electric Buffet Entertaining,” “Meal Magic with Shredded Wheat,” “Lively Ways to Serve Doughnuts.” In “Want Something Different?” we find 48 new Jell-O recipes,  including the tasty salad of lemon Jell-O and canned peas that I mention in the book (there’s an even better one called Jellied Orange and Cheese Salad, but I figured no one would believe it). In addition to the fine recipes, these booklets contain artistic wonders, such as a picture of a solicitous butler setting a mountain of Jell-O before his ballgown-clad mistress, who—clearly in a famine-induced stupor—gazes listlessly at the viewer. My favorites, though, are this cadaverous—but happy!—couple, dining on Jell-O.

including the tasty salad of lemon Jell-O and canned peas that I mention in the book (there’s an even better one called Jellied Orange and Cheese Salad, but I figured no one would believe it). In addition to the fine recipes, these booklets contain artistic wonders, such as a picture of a solicitous butler setting a mountain of Jell-O before his ballgown-clad mistress, who—clearly in a famine-induced stupor—gazes listlessly at the viewer. My favorites, though, are this cadaverous—but happy!—couple, dining on Jell-O.

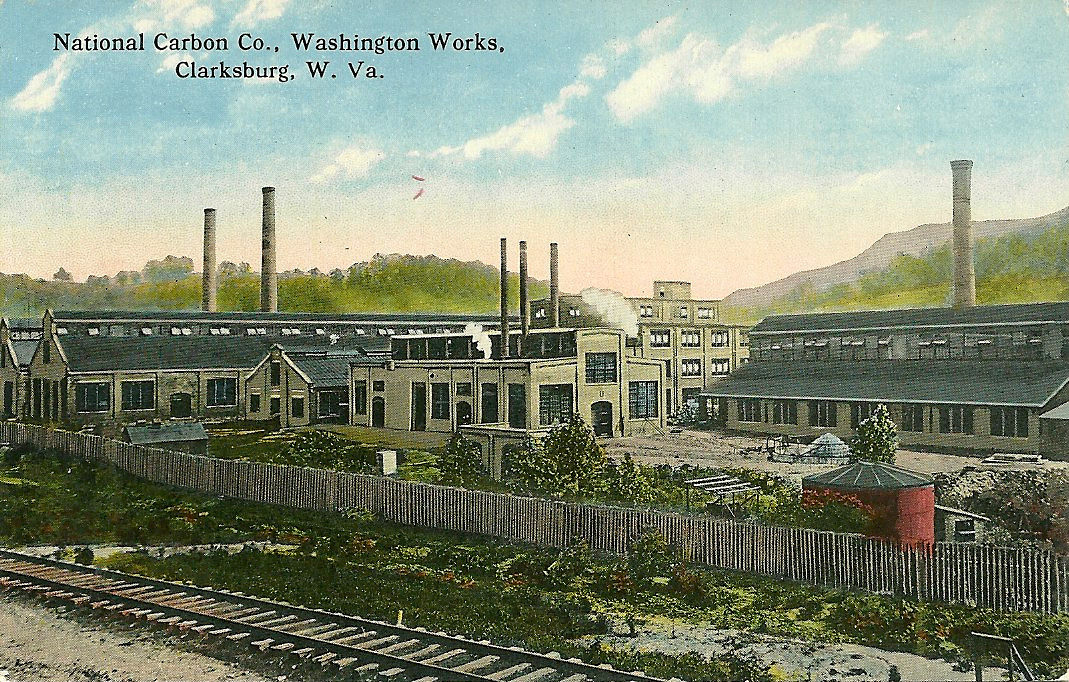

As one of my main characters was working for the Federal Writers’ Project, materials from the Project were obviously prime resources. The state guide, West Virginia: A Guide to the Mountain State, was invaluable for a number of reasons—where else would I have learned that West Virginia was, from the first World War until the late thirties, home to a robust chemical

industry, a fact that inspired Felix’s occupation? Where else would I have learned that the United States Fish Hatchery was in Leetown, well within range for a date for Felix and Layla? Nowhere. But much more interesting to me were the hundreds of place and event names it contains. I borrowed from these names liberally for Macedonia and its surroundings, as well as using the brief histories recorded in the guide for typical local knowledge, mental landscape, for my Macedonians. More useful still was Historic Romney, a booklet of town history produced by the Federal Writers Project in 1937, which modeled for Layla’s History of Macedonia, not only in the selection of material deemed fitting for inclusion, but also in its tone.